Science and Medicine

This week Silke spoke with Laura Massey about her first catalogue since she joined Shapero Rare Books to set up the Science department. Science and Medicine features 110 items spanning several subjects including Islamic Manuscripts, Sir Francis Bacon, Anatomy, Earth Science, Evolution, Mathematics, Astronomy and more.

Laura, you've managed to cover a huge variety of science areas in this catalogue. Which one is your personal favourite and why that area?

I've always been fascinated by modern physics, especially nuclear physics. This may be due in part to growing up at the end of the arms race and also hearing about the Chernobyl disaster from a young age. But there's a family connection, too. Like thousands of other young people from the Southern Appalachians, my grandmother worked at the Oak Ridge Manhattan Project site during World War II – important regional history that I began exploring in depth as a university student in the history of science. I'm particularly pleased to have a copy of the Smyth report in the catalogue (item 105). This was the first official account of the Manhattan Project, published in a limited lithoprint edition for staff, government officials and the press shortly after the bombs were used against Japan. It's a document that I find strange and evocative, representing a pivot point where government policy on atomic weapons and nuclear secrecy could have gone in a number of ways.

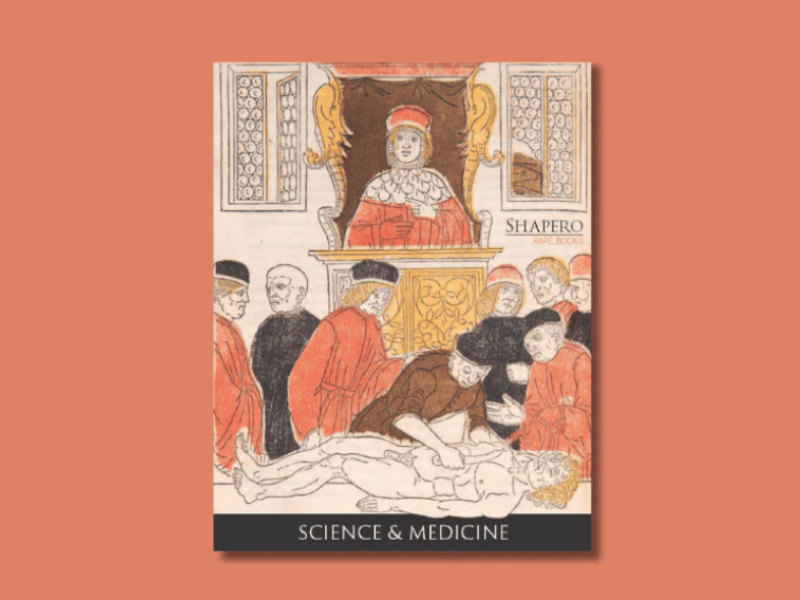

There are some real blockbusters included in the catalogue and I am not surprised that Ketham's Fascicolo di Medicina, the first Italian language edition with the rare colour-printed dissection plate, has already sold. I found Luca Pacioli's Summa de arithmetica rather fascinating. Tell us a bit more about its importance.

The Pacioli is fantastic, and perfect for someone like me who's more interested in applied than pure mathematics. Essentially, it was the first great mathematical encyclopaedia, covering arithmetic (including a wonderful plate illustrating finger counting), algebra and geometry. But what's really special is that it has a chapter on business mathematics that includes double-entry bookkeeping, essentially introducing the technique to Europe. This may sound banal, but in the 16th century it was revolutionary, allowing for much more complex business dealings and, together with the advanced credit instruments developed at the same time by Italian banks, it was the foundation for modern capitalism. The Summa also represents the first printing of any of the works of the famous mathematician Fibonacci and his friend, the artist and mathematician Piero della Francesca.

You have structured the catalogue starting with Islamic Manuscripts and probably unsurprisingly finishing with Technology & Computing. What is the reason you gave the Islamic manuscripts such importance?

When we were devising the order we had to consider whether the Islamic manuscripts should be grouped together or split into the general categories of astronomy, mathematics and medicine. I felt that the best choice was to place them together at the beginning. Not only because they include the earliest items in the catalogue chronologically, but also to emphasise the important role that Islamic cultures of the medieval and early modern period played in both developing new scientific ideas and preserving and transmitting older classical knowledge. I also wanted to separately highlight the contribution of my brilliant colleague Roxana Kashani, who was responsible for buying and cataloguing all of them!

You have 34 items in your Medicine section, ranging from £150 to £150,000. There are so many amazing books, maps and ephemera included, all instrumental in taking medical science to a new level. Which one impressed you most?

I know you've already mentioned it, but I love the 1493 Fascicolo di Medicina. It contains a plate that is likely the earliest printed depiction of a human dissection, and also one of the first three examples of colour printing. I'm really interested in the history of anatomical illustration, so this was a dream book for me for years.

But I also want to point out some of the lesser-known volumes, in particular two works on public health. John Haygarth's Inquiry How to Prevent the Small-Pox (1784) encouraged doctors to view the disease as a preventable communicable illness rather than an uncontrollable 'natural' one. In addition to promoting inoculation, it introduced the idea of contact tracing with isolation. This was backed up by work Haygarth did in Liverpool that reduced local case numbers by half, an incredible achievement.

A few decades later Edwin Chadwick, Secretary of the Poor Law Commissioners, appointed a team of physicians to investigate disease in Whitechapel. The report they produced was the first to recommend national responsibility for drainage, clean and paved streets, light and water supply, and a national health service. It was the direct precursor to modern social programmes, and was described as 'staggering' by Printing and the Mind of Man. Public health and epidemiology have been long-term interests of mine, but it's meaningful to consider these books now, five years after the pandemic and when questions about government responsibility for public health and medical research have achieved new urgency.

Natural History is obviously also included, and any good catalogue covering this has to have a Gould of course, but tell us about some of the lesser-known books or manuscripts. I love the early Victorian one!

It's wonderful! I've never handled a natural history manuscript that's both so extensive and so beautifully made. It dates to the 1830s in southern England and includes 326 delicate watercolours of animals and plants. Not just the garden-variety species usually seen in these documents, but unusual creatures like salamanders, bats and a slow worm, less recognisable birds such as the nightjar, and even a carnivorous sundew. These are complemented by the maker's notes about their behaviours and habitats and where he obtained specimens, which is also unusual – notes copied from books are much more common in these types of manuscripts. I'm really pleased to report that this one is (fingers crossed) going to an institutional collection.

Another great item from the natural history section is more recent. It's a set of pocket notebooks documenting eight years of intensive birdwatching by an Audubon Master Birder on Long Island in New York. For every outing he noted the date and time, weather conditions and topography, all the species he saw, and whether they were new additions to his life list. As a participant in the Master Birder Program he both led and attended organised birdwatching outings, some to other states and countries, and details of these are present (sometimes including receipts). There are also records of the birds coming to his backyard feeders, and little flashes of personality like the announcement of his first day of retirement. On a personal level this is a charming set of notebooks, but these types of records are also useful for documenting changes in species and habitats over time.

The most expensive book in your catalogue is of course Darwin's Origin of Species at £300,000. What makes this one so special, and do you think this is the one book that attracts interest from a wide range of collectors, not just those interested in evolution?

Absolutely. There are just so many ways of looking at Origin as a collector. On a scientific level it's foundational to aspects of modern life like genetics, medicine, ecology and environmentalism, not to mention eugenics and scientific racism. The book has a fascinating publishing history, with the alterations in Darwin's thinking visible in the textual changes. And the large number of editions in his lifetime means that significant copies are available in a range of prices, making it accessible for beginning collectors. But I think what's most appealing is that it's one of the key works of human thought, equal to Newton and Copernicus in the way it changed our understanding of ourselves and our place in the universe.

Your Astronomy & Space section ranges from Piccolomini and Galileo to 1970s Soviet space art. Which one did you find most astonishing?

The 1926 Edwin Hubble offprint is unbelievable. He was only a few years out from his graduate work and had just proven that there are galaxies outside the Milky Way, and already he was thinking about how to use this fact to understand the large-scale structure of the universe. This paper contains three fundamental discoveries that revolutionised astrophysics: the distribution of galaxies in the universe, the density of mass in the universe, and the application of Einstein's work to the structure of the universe. It's a breathtaking chain of logic, each assertion building creatively on the one before.

I have been meaning to ask you about women in science, and your Chemistry & Physics section includes a small group of original artworks of women chemistry students in Oxford in the 1920s by pioneering chemist Muriel Tomlinson (1909–1991). Tell us a little bit more about it and any other highlights connected with women scientists.

Thanks for asking about this – exploring women in science is such an important and enjoyable part of my work as a bookseller. It's very easy to think this means a handful of superstars like Marie Curie, but there have been so many women doing the unglamorous day-to-day work of science, just like their male colleagues. One of these was Tomlinson, who showed early talent at chemistry and was educated at St. Hilda's, Oxford. She completed a PhD and then became a lecturer in Cambridge, before rejoining St Hilda's where she established the biochemistry department. She also seems to have been interested in art, and in the catalogue we have a set of 15 pencil drawings of women working with laboratory equipment, teaching and sitting exams, likely from her education during the 1920s. These come together with other drawings and linocuts she produced.

Another highlight are the first two editions of Louisa Lane Clarke's The Common Seaweeds of the British Coast and Channel Islands (1865 and 1881). I'm fascinated by Victorian seaweed and fern collecting culture, particularly the ways it offered women socially sanctioned opportunities to study biology, enjoy the outdoors and in some cases attain semi-professional scientific standing. Both the drawings and the seaweed books are a reminder that women have always done science for their own edification and enjoyment, even when professional opportunities were more limited than today.

You finish with the Technology & Computing section. Staying with the women scientists, tell us about Grace Murray Hopper, who helped realise Babbage and Lovelace's analytical engine.

Hopper was, as one of my colleagues exclaimed, 'a total badass' and one of the founders of modern computing. She earned a PhD in mathematics at Yale and, when World War II began, enlisted in the US Naval Reserve and was posted to a computational project at Harvard. This was Howard Aiken's Mark I, one of the earliest general-purpose electromechanical computers, which has been described as bringing the principles of the Analytical Engine to full realisation. Hopper helped write the guide to the Mark I, A Manual of Operation for the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator, and this is considered to be the first computer manual. After the Mark I she had a long and very productive career, but her most important contribution was the concept of machine-independent programming languages, the basis for computing as we know it today. She remained enlisted in the Navy for over 42 years, achieving the rank of admiral, and in addition to numerous military commendations was awarded the US's highest civilian honour, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

And my final question – which of the 110 items in your catalogue surprised you most?

I was delightfully surprised by the palaeontology manuscript by Robert Nicolet. I saw it sitting on a stand at a book fair and instantly knew it was something special. First, because amateur manuscripts about palaeontology are so uncommon, and then because the artwork was outstanding – lovely, sophisticated linework and outstanding composition. The final page in particular is fantastic, a visual depiction of the history of life on Earth so striking that I used it as the front endpaper of the catalogue.

Many of the illustrations are dated between 1916 and 1918. Nicolet was relatively young at the time and originally from Switzerland, as evidenced by additional family material included with the manuscript. But he seems to have visited Belgium because the frontispiece depicts the Bernissart Iguanodons at the Museum of Natural Sciences, with a figure that may be himself busily sketching in front of them. Was he doing war-related work and spending his free time looking at fossils? Was he perhaps a commercial or graphic artist? And was the manuscript done purely for his own pleasure or as a maquette for a planned publication? There may be additional surprises waiting for the right researcher!

Download the e-catalogue here >

Browse the catalogue online here >