Modern Firsts (For Beginners)

A book fair can be a dizzying experience for the collector of modern firsts, particularly one as big and prestigious as the ABA summer fair, now called Firsts. It’s public, it’s private, it’s whatever you want to make of it but above all, it involves real people. In short it’s not ‘online’, which for many is probably the forum of which they have most experience.

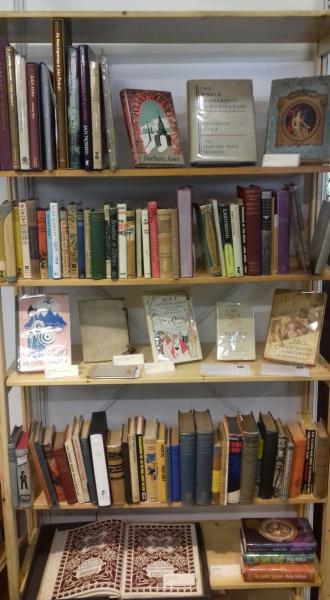

To begin at the beginning: why collect modern firsts? Because you’re likely to have read (and enjoyed) the writer’s work, because the first edition of anything represents the spark that lit the fire, because the dust-wrapper (like a record sleeve) can be dazzling, because a run of them looks good on your shelves and because it’s something to be proud of. Looking at it from another angle, to collect second editions would just be perverse.

It’s possible that for collectors whose interests belong to an earlier time, where contemporary editions are sufficiently uncommon to command significant value, the cult of the first edition has its own look of perversity – certainly it has a range of its own fetishes. Primary amongst these is the dustjacket, but it extends to wraparound bands, laid-in material and the like, particularly where these represent the form of the book as it was first issued. They may have been added back on or in by dealers or collectors who have an interest in enhancing their copy, much as one’s orange juice may be served ‘avec sa pulpe’, and whether this is acceptable to you or not depends on your take about purity. It has to be said that the temptation to market the fully-accoutred book as ‘with bits’ is strong.

It is the ‘as issued’ quality that explains the supremacy of the first edition: it gives us the form of something when it first enters the market – for the life of a book as a commodity is its commercial life, neither more nor less. Versions of the text necessarily precede the first edition – be they plot sketches, drafts or proofs of various types – and these all form part of the prehistory of the book. They are of both scholarly and bibliographic interest and when they surface at auction invariably command a good price if a book has become famous.

‘First edition’ is really a short-hand term to refer to the first printing – for properly speaking an edition corresponds to a setting of type. The field of modern first editions is bedevilled by minor aspects of major significance, with regard to issues or states (the terms are not interchangeable) of the textual and the paratextual material, or the binding (including, and often predominated by, its most extraneous elements) – so that even within the apparently absolute category of the first edition there is a hierarchy, a scale of priority that brings its own little puzzles.

When Hammond and Anderson compiled their Tolkien bibliography, they assumed that the state of The Return of the King with slipped text on p. 49 was the first and that the error was then corrected. Subsequent evidence has led the bibliographers to update their position and to regard it as an error that crept in. Therefore it becomes the second state (the bibliography itself has yet to be updated.)

Another example: Joseph Heller’s memoir, Now and Then, features a numberline on the verso of the title-page – one of the possible carriers of the edition statement – but, a publisher’s letter accompanying some copies clarifies that ‘due to a production error this first edition [...] appears on the editions page to be a second edition. This being an insoluble problem – we cannot reprint the first edition, because it would then be the second edition [...], we have asked Joseph Heller to mark and initial a 1 on the editions page’ – did somebody say ‘Catch-22’?

This is all good sport for scholarship and sometimes for ridicule. In 1066 and All That, Sellar and Yeatman describe, in a ‘Preface to the Second Edition’ that has been there since the very first printing, how ‘A first edition limited to 1 copy and printed on rice paper and bound in buck-boards and signed by one of the editors was sold to the other editor, who left it in a taxi somewhere between Piccadilly Circus and the Bodleian’.

Only a fraction less elusive than apocryphal editions are those éditions mythiques that represent the genuine rarities, not predicated on condition or any sort of supply-demand bargaining, of this world: known copies of the suppressed first printing of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland are few and finite – of fifty possible copies, twenty-two are recorded, of these only five are outside institutional walls (and therefore capable of coming on to the market). Presentable copies of the first published edition are, rather like copies of 1066 and All That in its dustjacket, elusive enough.

The key attribute of the first edition, in basic terms, is its universality: every published work has a first edition; some, even collectable ones, have nothing more. The vast majority of these – the age of mass-publishing has been long – have no significance to the bibliophile. The category of books that are both compelling and genuinely scarce is a small one. The modern firsts collector is seldom on the trail of rare books per se, but rather of copies possessed of a rare quality, be it their condition, dust-wrapper, illustrator, an association with a previous owner – there are many reasons for a book to be desirable to a collector.

Do I need a lot of money? If you’re aiming at the top, the Tolkiens, Flemings or Rowlings, then you do. But most people start with modest ambitions and these are often formed by a visit to your local high-street bookshop. What’s selling? What’s been well reviewed? Who are the award winners? (A word of caution here. Winning the Booker Prize is the kiss of death for most books. Many authors’ contracts forbid the publisher to enter the book for it.) The losers far outnumber the winners. The majority of novels falter early in the cycle, and spend their short lives – like many of the shops that house them – hovering over one abyss or another. Something like 90 per cent of publishers’ royalties are paid to about 10 per cent of their authors.

That brings me to the last and best reason to collect modern firsts: the excitement of it all, the challenge inherent in pitting your judgement against that of the herd. One key to success is determination, a retentive memory and stout shoe leather. Another is to go to ‘Firsts’ and see what’s for sale.