Illustrated: Social Posturing in the Edwardian Bookplate

Lauren O’Hagan is one of our valuable, regular contributors. She recently completed a PHD in Language and Communication at Cardiff University and works as a research assistant for the Object Women digital archive and as a freelance translator.

For our Winter 2020 Issue Lauren wrote ‘Social Posturing in the Edwardian Bookplate 1901–1914’ in which she discussed a number of specific bookplates from the period. Because we were squeezed for space, we were unable to illustrate the article with the full suite of images to which she referred. So that you can appreciate the originality and depth of Lauren’s work, we have the greatest pleasure in reproducing them in full here. The complete text of her article can of course be found both in print and online.

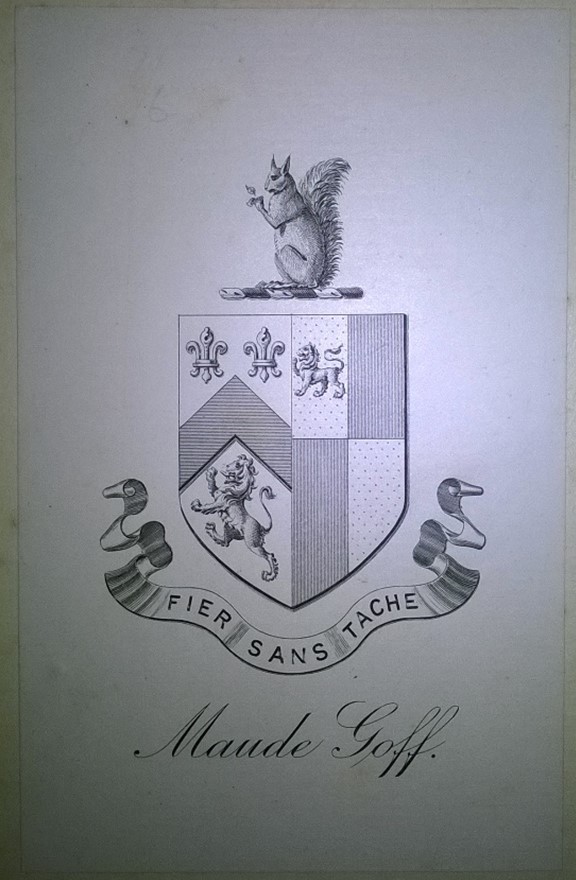

Fig. 1: (appears in print as Fig. 1, p665)

“First and foremost, as a woman, Maude had no legitimate claim to a coat of arms. The rules of the College of Arms state that ‘coats of arms must be descended in the legitimate male line from a person to whom arms were granted or confirmed in the past.’ Secondly, archival records show that Maude Goff was a housemaid and daughter of an agricultural labourer. Although she rose up the social scale to lower-middle-class upon her marriage to a shopkeeper in 1907, she did not have the financial or social means to possess an authentic armorial bookplate. Furthermore, closer inspection of the elements of Goff’s bookplate reveal that they are largely an assortment of pseudo-heraldic symbols that do not adhere to the fixed rules of heraldry. The crest, for example, is the non-characteristic red squirrel. Here, the squirrel serves as a rebus rather than a real emblem, ‘Goff’ deriving from a Welsh nickname for someone with red hair. The shield itself shows an unusual blending of two coats of arms: a chevron containing two fleur-de-lis and a lion, and a quarterly containing a lion. Although the symbols on the left are historically associated with the Goff family, the College of Arms database shows no connection between this coat of arms and Maude Goff’s own family.”

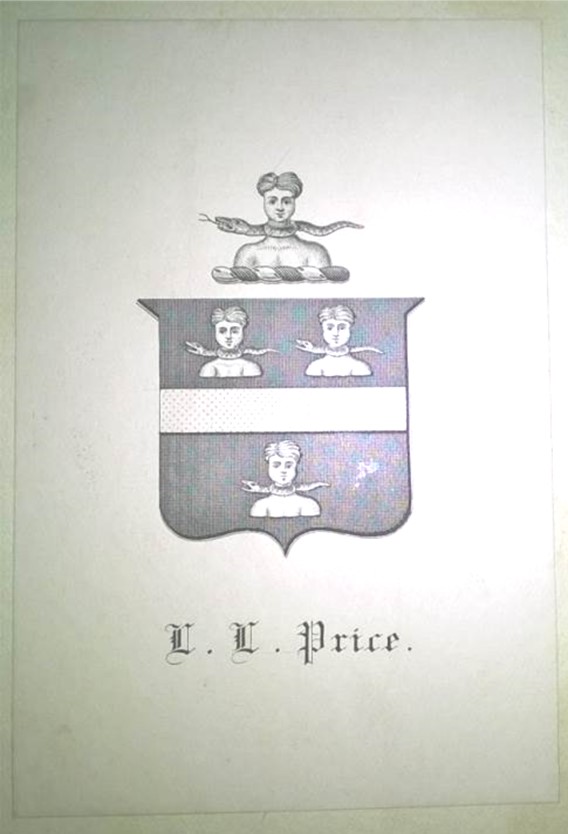

Fig. 2: (did not appear in print)

“Langford Lovell Price, an economist and examiner in the moral sciences tripos at Cambridge University, also combined erroneous symbols to create his own armorial. Again, the College of Arms database confirms that Price was never legally entitled to a coat of arms. This may explain why, despite having the financial means to afford an artist-designed bookplate, Price opted instead for an armorial designed by a stationer. The dubitable authenticity of Price’s bookplate is reflected inthe various attributes of the coat of arms that, in fact, come from the lineage of the Vaughans, not the Prices… Working and socialising in an upper-class environment, Price may have felt the need to fit in and used social posturing to do so. Given his relatively high social status and reputation, it is likely that most Edwardians who came into contact with Price’s book would have accepted his bookplate at face value, and thus accorded him with the corresponding cultural capital.”

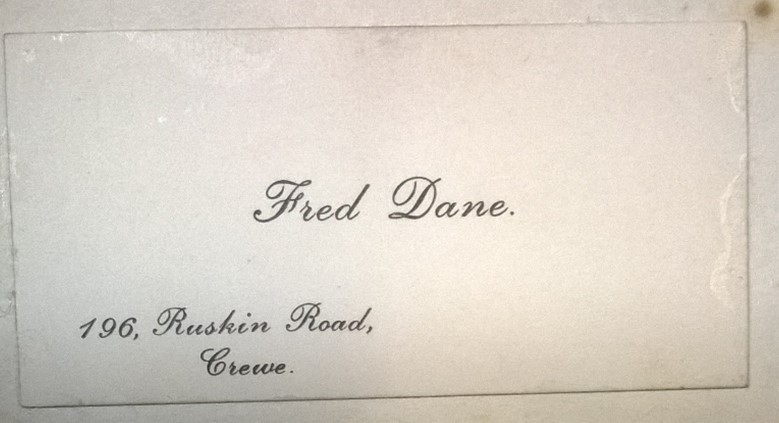

Fig. 3: (did not appear in print)

“Self-made bookplates were typically created from business cards or calling cards. These cards were chosen because they shared many characteristics with traditional book labels (e.g. lack of bordering and image, rectangular shape, central position of the owner’s name), so they could be easily transferred into this new context without anybody realising their original purpose. The recontextualization of business cards or calling cards was particularly common amongst clerks (such as this example from Fred Dane, clerk) and may have been a defensive response to a sense of threat. Therefore, while we may read these self-made bookplates as a sign of their wish to signal wealth associated with a condition higher than their own, these marks can often, in fact, betray their anxiety and uncertainty at belonging.”

Fig. 4: (did not appear in print)

“For shopkeepers, self-made bookplates were typically made from shop paper bags. Owners cut their names out and affixed them to the endpapers of books (see this example of William Straw, grocer). Like business cards, shop paper bags also shared a physical similarity with book labels, which made them easily transferrable.”

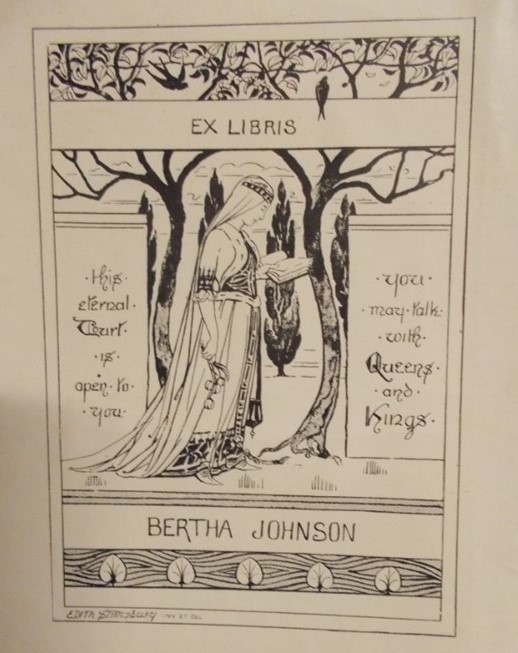

Fig. 5: (appeared in print as fig. 2, p 669)

“For Edwardians with more disposable income, custom-designed bookplates offered an opportunity for them to posture their educational level. It was not uncommon, for example, for pictorial bookplates to show shelves of books by canonical authors or images of literary figures to communicate the message that the owner was well-educated. This is particularly apparent in the bookplate of Bertha Johnson, the principal of the Association of Home Students (St Anne’s College, University of Oxford). Her choice of image and quote come from John Ruskin’s Sesame and Lilies – a book that had a tremendous influence as a self-help book for middle-class Edwardians. The quotes used are preceded in Sesame and Lilies by ‘Will you go and gossip with your housemaid or your stable boy when…’ and ‘jostle with the hungry and common crowd for entrée here, and audience there, when all this while…’When read through the context of the bookplate, it becomes apparent that the owner is expressing her distaste for communicating with the labouring classes, thereby equating herself with a higher status than she truly possesses.”

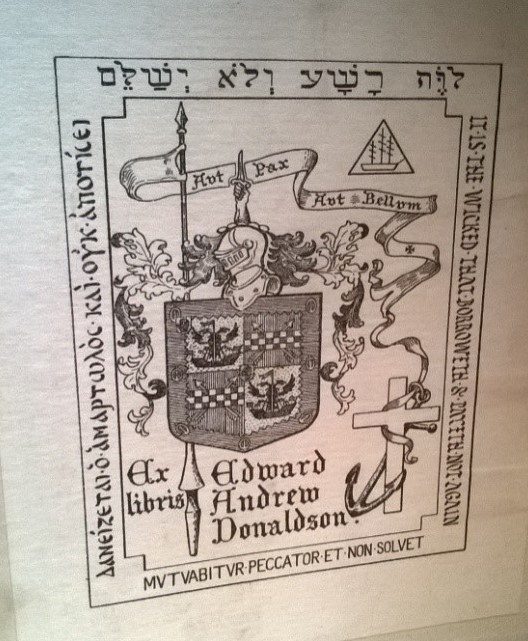

Fig. 6: (did not appear in print)

“Multilingual messages were also used frequently by some Edwardians to imply that they had knowledge of several languages and thus were intelligent. However, these multilingual inscriptionsare often incorrectly transcribed. The bookplate of Edward Andrew Donaldson, for example, has the message ‘it is the wickedeth who borroweth and payeth not again’ written in English, Latin, Greekand Hindi around its borders. The Greek and Hindi examples, however, are grammatically inaccurate. As with most cases of social posturing, the owner’s concern is with the identity display itself rather than the actual message.”

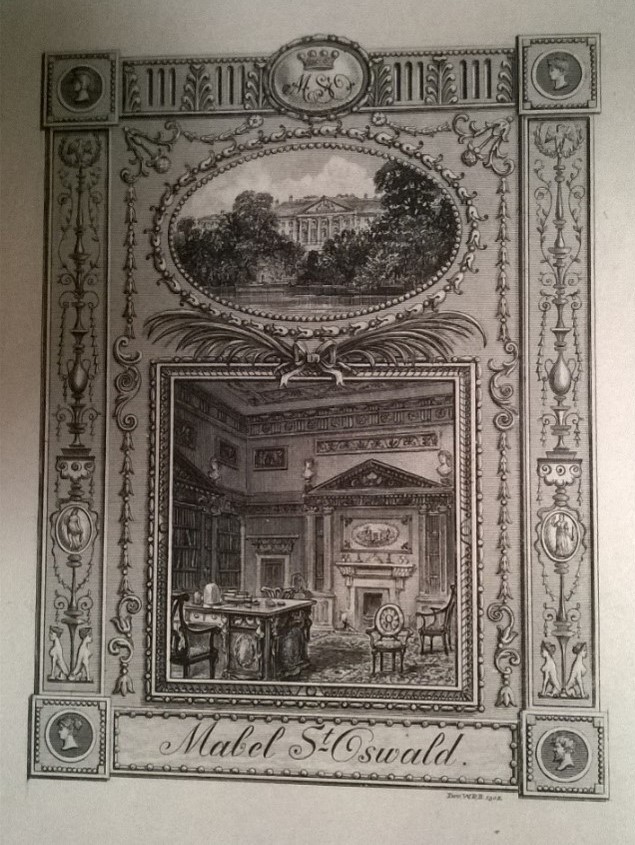

Fig. 7: (appeared in print as Fig. 3, p. 671)

“Throughout the Edwardian era, personal possessions were treated as weapons of social distinction that spoke to the outside world of a person’s social status. Consequently, those with the financial means used their bookplates to showcase their homes, furniture and ornaments to anybody who came into contact with their book.The bookplate of Mabel St. Oswald, a baroness and the wife of Rowland Winn, a Conservative politician and baron, is a clear example of this. St. Oswald’s bookplate shows an image of her house, Nostell Priory, and her large collection of furniture, which was allmade exclusively for the house by Thomas Chippendale. Modern day images of the house, now a National Trust property, show that the image is a faithful replica of the room.”

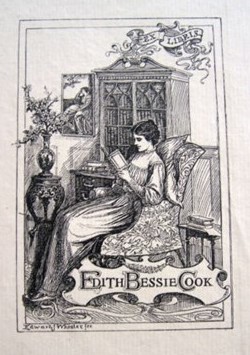

Fig. 8: (did not appear in print)

“As these bookplates were privately commissioned, owners could choose what elements to include and what elements to miss out, or even add details that did not really exist in order to reflect on themselves favourably in posterity. A case in point is the bookplate of Edith Bessie Cook, a headmistress from Leeds. Not only does it show furnishings and decorations outside of her financial means and social status, but it also displays a self-portrait in a mode of dress associated with the class above her. Self-portraits offered overt opportunities to social posture, using clothing, jewellery and hairstyles. Owners often chose to depict themselves as saints or historical figures, or made themselves more handsome or pretty than they actually were.”

Read O’Hagan’s full article by logging in and viewing our Winter 2020 Issue.

If you are not yet a subscriber, contact info@thebookcollector.co.uk, to request temporary access to this article via our digital Reading Room.